Johann Heri[1] was born on June 24, 1778, the fourth of seven children born to Johann and Anna Heri. Little is recorded of the early life of Johann. We do know that the family resided in Niedergerlafingen. It can be surmised that life was quite difficult as both parents outlived four of their children.

Politically, life was also difficult in Switzerland during this period. The French, under the direction of Napoleon, had annexed a portion of the country. Besides being forced to allow the French to use the roads for military purposes, the Swiss also had to supply their young men for French military service.

As a Napoleonic Soldier

It is not clear if Johann was one of these Swiss mercenaries constricted to fight for the French. Possibly he was a hired soldier because documents from a later part of his life refer to him as “Wachmeister.” This title referred both to a sergeant of the city guard, the person charged with fire watching or a sergeant in the military guard. Supposing the later is the correct one in Johann’s case, it is unlikely that such a title would be given to someone who was forced to fight in the army which had conquered one’s homeland. It is more likely a title to be given to someone who had been hired for that purpose.

Other evidence suggest that Johann enjoyed the possibilities that military service provided. The 1961 family history refers to Johann as having a “spirit filled with the love of adventure. Adventure was to be found in war.”[2] That family record also says that Joseph went to France in order to become a soldier in Napoleon’s army.

It is not clear exactly when Johann served in the army. While Napoleon was given command of the artillery of the army of Italy in February 1794 and Johann is known to have been in Switzerland in early 1813, the family tradition holds that Johann fought against the Austrians. At the end of 1805, in the most brilliant of his victories, Napoleon beat the Austrians at Austerlitz.

In later years, Johann told the story of the night the army was encamped close to the enemy, before the battle that was to begin as a surprise attack the next day. Napoleon ordered a “cold camp” that night, with no watch fires or cooking fires, and no lights. Making his rounds late that night, Napoleon found a soldier who had rigged up a night light, a shaded candle so protected that its rays could not be seen from a few feet away, and who was writing a letter by the tiny glow.

“What are you writing?” asked Napoleon.

“A letter to my wife,” the soldier replied.

“Tell her you are to be shot at sunrise for disobeying my orders,” said Napoleon and then he continued on his rounds.[3]

Johann and Wulf

Johann became acquainted with a man named Wulf, and they were constant companions. Wulf was savage and ruthless, and feared nothing. Johann found adventure with Wulf.

As Napoleon’s army tramped over the country, plundering and sacking each town in its way, swift runners would race ahead of the army to other towns to warn the people that the enemy was coming. Then the people would flee to the hills and remain there until the army had passed through their city.

For some reason, lost in the midst of time and the twisted convolutions of Napoleon’s mind, orders had been given to kill every person in these towns, and those who were unable to flee died there. In one such deserted town, Johann was going through one of the houses when he heard a tiny cry. He thought the sound came from beneath the bed, and when he raised the spread, there was a baby in a basket, undoubtedly shoved under there hurriedly as its parents gathered their other children for a flight to escape death, with the thought that no one would be inhuman enough to harm a baby. The little tot smiled at Johann, and though he was disobeying Napoleon’s orders– an action punishable by death– he could not harm the harmless little thing, and shoved it back under the bed with an unspoken prayer for its safety. Then he went down the street to the next house, and the next.

Later, when the entire town had been searched, Johann looked about for Wulf. Seeing Wulf walking toward him down the street, Johann started toward him. Wulf had his rifle over his shoulder. To his horror, Johann saw the baby he had spared– skewered on Wulf’s bayonet.

When the men were discharged from the army, they were allowed to keep their uniforms and their swords. Johann and Wulf started home together. Soldiers returning from battle were always welcome in any home in any town, as they were the newspapers of the day. So it was that as Johann and Wulf entered a town one night they chose the finest house at which to ask for a night’s lodging. The two men knocked at the door, which was opened by a woman in mourning dress.

In answer to their request for lodging, she said, “I would very much like to entertain you gentlemen, but I must warn you first. My husband died yesterday, and unless I pay a great amount of money to a group of men who say that my husband owes it to them, two devils will come and take him away.”

To this, Johann replied that he was a religious man and he could have nothing to do with devils. However, a situation of this kind was a challenge to Wulf, and he told the widow, “If you will give me bread and all kinds of cheeses and wines, I’ll stay with your husband tonight and no devils will get him.”

Johann went to find other lodgings, but Wulf remained. The woman set beside the casket a table loaded with the best foods, and after Wulf had sent the woman to bed, he sat down to his all-night feast. Time passed and nothing happened. Then exactly on the stroke of twelve, the outside door slowly opened. Wulf stood up and placed his hand on the hilt of his sword. The door opened a bit farther, and then suddenly it was flung wide open and two devils leaped into the room. One devil ran to the foot of the casket and the other ran to its head. They reached for the dead man.

Wulf said, “Men, put down that body.” But the devils only took a firmer hold on the corpse.

Wulf repeated. “Men put down that body.” The devils took no heed of the warning and started moving toward the door with their burden. Wulf said no more, but he swung his sword and the head of one of the devils fell to the floor. This was an unexpected turn on events for the interlopers, and with a yell the other devil, dropping the body, leaped for the door. Wulf could not catch him, but a mighty swing of his sword cut a deep gash down the devil’s back. His duty done, Wulf finished his meal.

Early the next morning the lady of the house appeared, anxious about what might have occurred in the night. “Is the body still here?” she asked.

Wulf replied, “Not one, but two corpses now.”

The man who was wounded was easily tracked to his home by the blood he shed from the gash Wulf had given him. Thus the attempt to gain possession of the widow’s money was foiled.[4]

Marriage to Maria Barbara Fluri

Having returned to his native Switzerland, his desire for adventure satisfied, Johann settled down to establish a family. In 1812, he tried to become a citizen of Niedergerlafingen. In the Swiss system, those who were already citizens had the right to vote on those seeking citizenship. At this time, they believed there were already too many citizens for the available land. In 1816, Johann brought a lawsuit against Niedergerlafingen over this question.

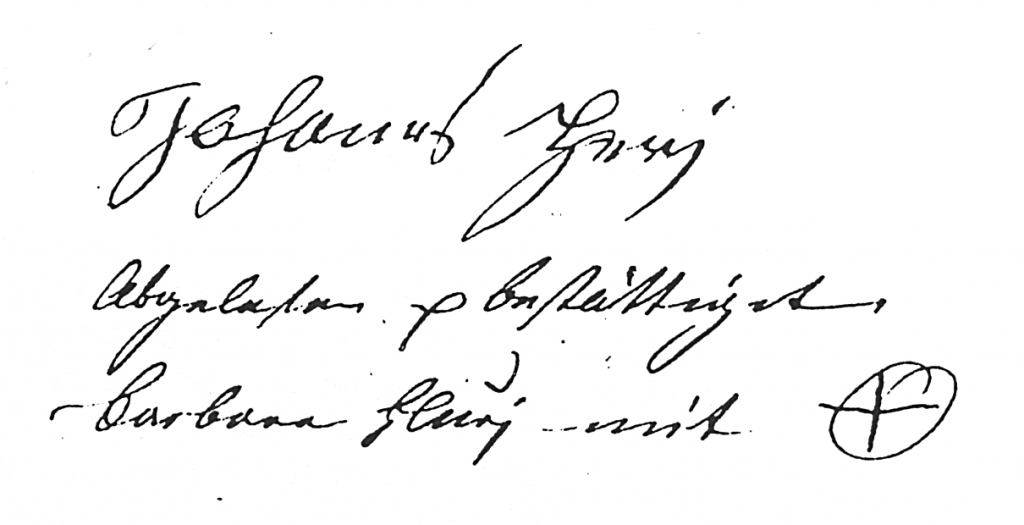

On February 5, 1813, he married Maria Barbara Fluri from the village of Horriwil. She was 23 years old, having been born to Johann Jakob Fluri and Elisabeth Gerber on December 1, 1740 in Unterhorriwil.

The Fluri family was experiencing difficulties at this time also. The registry for passports has several entries for Fluris. Their emigration could have been a consequence of their religious beliefs. Many members of the family were Anabaptist. Among other things, Anabaptists proscribed adult baptism which was contrary to the belief of the Reformed Church in Switzerland. If the child were baptized, the Anabaptist proscribed a re-baptism in adulthood. The idea of one person having two baptisms as well as their extreme individualism in religion brought Anabaptists into conflict with the Catholic Church.[5]

No indication was found of where Maria Barbara stood on this issue was found.

Children

This marriage produced 12 children. Because of the poor living conditions and medical care in comparison to today, five of the children are known to have died before reaching adulthood. The oldest surviving child was Urs Viktor who would eventually immigrate with his own family to the United States. Another son, Urs Josef Alois, was born deaf and dumb.

Johann Heri, the ninth child of Johann and Maria Barbara became involved in a couple of legal issues. The first legal problem resulted from the Catholic Church’s decision in 1870 to officially accepted the doctrine of infallibility. The acceptance was not universal. In the very Catholic area around Solothurn, it caused a deep split. The controversy involving Johann came about because a teacher in Niedergerlafingen was following the “new” Church and teaching that there was no devil. Johann did not want his son attending such lessons and allowed the child to stay home. As a result, he was fined for the 33 absences in 1876 and 1877.

Johann then sent his son to Kriegstetten to get what he believed was proper training. He also appealed the penalty of 92 Sfr to the Bundesdath. The decision rendered on April 26, 1879 and signed by the President of Switzerland, agreed that Johann did not have to pay. It held that the country’s constitution guaranteed that the father of a family had the right to decide the children’s education.[6]

In 1872, nine years before his death, Johann’s second famous legal problem came about. His land was taken by the government so that a school could be built. Johann held them off with a gun. Police were called in.[7]

Hieronimus (Jerome) Vincent, Johann and Maria’s youngest son, would also immigrate to the United States, at least three times. At least one of those times he was in New Orleans, Louisiana. Passport records sometimes provide sketchy ideas of what early family members looked like. Hieronimus’s record show that he had brown hair, a round forehead, brown eyes and an average sized nose and mouth. His face was described as being oval.

The Family Residence in Niedergerlafingen

The story of the home of Johann and Maria Fluri provides one of the more interesting stories of the family history. The original house was a large, one story building at Number 36 in Niedergerlafingen. It had cost 2,000 LIV to build in 1821. Although no drawing of this house is known to exist today, it most likely was designed with space for the family to live in and other areas given over to the housing of farm animals and storage of feed and farm equipment.

This original residence burned down on Sunday, December 18, 1831. The couple had 8 living children at this point. The exact cause of the fire remained unknown but the efforts of the civil officials to record the various eyewitness accounts provides some fascinating reading.[8]

Johann Heri remembered the events of that day in his testimony to the investigating officials:

Yesterday, my servant and my son Johann Josef and others who live in the house went to church in Kriegstetten. At 11:30 A.M. we had lunch and when we finished the fire in the kitchen was out. I stayed with my wife and four children in the living room reading. Maybe at 1:30, I heard shouting in front of the house but I did not pay attention because it was time to go to church. Because the shouting continued, I went to the front of the house and saw the grain room and stalls were burning.

The shouting came from Barbara Schreyer, the 26 year old, unmarried daughter of Joseph Schreyer from Niedergerlafingen. She testified:

Today after one o’clock, I wanted to go to church in Kriegstetten with two of my sisters. When we were about 200 steps away from the house of Johann Heri, we heard a crackling sound and saw that the east side of the house was burning. That is the reason we started shouting. We did not go into the burning house.

She was certain that the fire started in the barn portion of the building because she didn’t see any smoke by the living quarters. She did not know how the fire had started however.

Maria Barbara Heri, Johann’s wife, was 42 years old at the time and remembered things much the same as her husband had:

How our house burned this afternoon, I cannot say because I was with my husband and four younger children in the living room when we heard shouting outside on the street. I went to the front of the house and saw the barn area was on fire. How and where the fire started, I do not know.

Shortly after the fire was discovered, many people became involved. Establishing the cause of the fire was the topic of the day. Apparently, the danger posed by cooking stove fires was ruled out early on, providing the opportunity for much speculation about the real cause of the fire.

Maria Heri recalled a visitor during mealtime:

When we were eating lunch, a daughter of Niederer came and begged for some food. We gave her a piece of bread. I cannot say if she started the fire because we saw her leave from the window.

Her husband Johann discounted the possibility of smoking causing the fire. He testified:

It cannot be from smoking. No one in the house is a smoker except the male servant but he only smokes after dinner and then only in the living room. The ashes from the smoking are always put in the cooking stove. Surely it did not start in the living area but in the animal area. I cannot say who is responsible for this accident. It could be someone set the house on fire.

However, because the living quarters was the last area to have burned and that is where he was at the time the fire was discovered, Johann did not feel that he could be of much help determining the cause.

A 26 year old carpenter, Johann Ege from a town in Würtenberzwichen, was working at Johann Affolter’s near the Heri home when he heard the shouting. He too testified about what he found when he came upon the burning house:

After lunch I did a drawing with Mathias Schill and then immediately we heard shouting that a house was burning. We both ran to the burning house and when we arrived, the roof on the eastern section was burning. There was no fire in the living quarters. We started helping to carry out the furniture. Others helped but when the flames reached the living quarters we had to get out. I do not know the reason that the fire started.

He was sure however that the fire did not start in the kitchen area because he saw no flames there. The man Ege was working with, the 26 year old Mathias Schill from Waldkirch von Baden, corroborated Ege’s account:

The barn part was in flames. The living quarters was not on fire so we carried out furniture. But after that, the flames spread and we had to leave. Without a doubt, the fire had to have started in the animal part because we did not see any fire in the living quarters at first.

Others pitched in to help save the Heri’s animals and possessions. Johannes Freÿ, the son of Johann from Niedergerlafingen freed the animals from the barn.

I did not see fire in the stalls with the cows but saw fire in the wagon area and in the pig area. I am sure the fire started in the wagon area. After he freed the animals, Johann Heri came out of the house and saw his house was burning.

A Kanton official, Urs Josef Affolter from Niedergerlafingen reported that he too had been involved in fighting the fire that day:

A Friedensrichter named Heri came to me as we heard shouting that there was a fire. We both organized the fire wagon and then other people came and helped. I went to the house and found smoke and fire in the wagon room. The living quarters was not on fire. By the way, the man who lost his house is rich and has never had trouble. He was always careful with fire and his lanterns. He always kept his stove clean so I am surprised that fire would break out in the afternoon.

There is a notation in the Kriegstetten-Schreiben papers that Johann Heri read what Affolter wrote and added that he didn’t think anyone started the fire.

Rich or not, Johann and Maria lost much during the fire. None of the children were hurt. However, besides the building which was their home, they lost all the animal feed, the straw, and Johann’s farming equipment. Much of the family furniture was apparently spared because neighbors carried it out before the residential part of the structure caught fire. But in the confusion someone also helped themselves to some money hidden in a draw of one of the furniture pieces. During his testimony, Johann mentioned the theft of silver pieces.

In a small room next to the living area, I had 150 silver pieces in a drawer in a cabinet and it is now missing. My son Viktor brought that drawer out of the house but the money is missing. I can not say who stole the money. My farmhand (Knecht) Josef Lutherbacker from Steinhof went to Solothurn right after lunch. Also my 14 year old son, Viktor,[9] was not in the house either and my servant was in the Kriegstetten church.

The identify of the thief was never determined. The Oberantmann declared that all the belongings were so heavily damaged that 2,00 LIV had to be paid by the insurance company.[10]

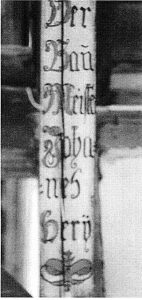

About a year after the fire, a new house, Number 44, was built at approximately the same location. It too was a combination residence and barn. According to one story, this new house was actually one that a man in Horriwil had torn down and moved to Niedergerlafingen. It was supposed to have been rebuilt in 12 days. This story is largely discounted by the family today. Regardless, on May 19, 1832, Johann was given permission to build a new house. This new building at Kriegstetten Strasse 14 is sometimes referred to in documents as the “Wachtmeister Haus #44.”

In the early 1980’s, it was no longer a family home but a Shell gasoline station. The farm land now contained a grocery store and apartment building. In the front of the Wachtmeister Haus was a newspaper kiosk. It is certain that this was the house that Johann and Maria built to replace the one destroyed in 1831. On the outside of the building, under the roof overhang were beams that had been painted. Inscribed on one beam in colorful paint was the notation “30 Mai 1832.” Another beam had the inscription “Der Baummeister Johanes Hery.” A third contained a prayer for blessing upon the house.[11]

The date on the beam is just 12 days after Johann received permission to build the house. This is probably the source of the story that the house moved from Horriwil was rebuilt in 12 days. Unfortunately the house was pulled down and the lot cleared in 1986. At first it was thought that all four beams were buried with the rubble. However, it was later discovered that neighbors had carried them off and at least one beam has been recovered and is now in the family’s possession.[12]

Johann’s Last Will and Testament

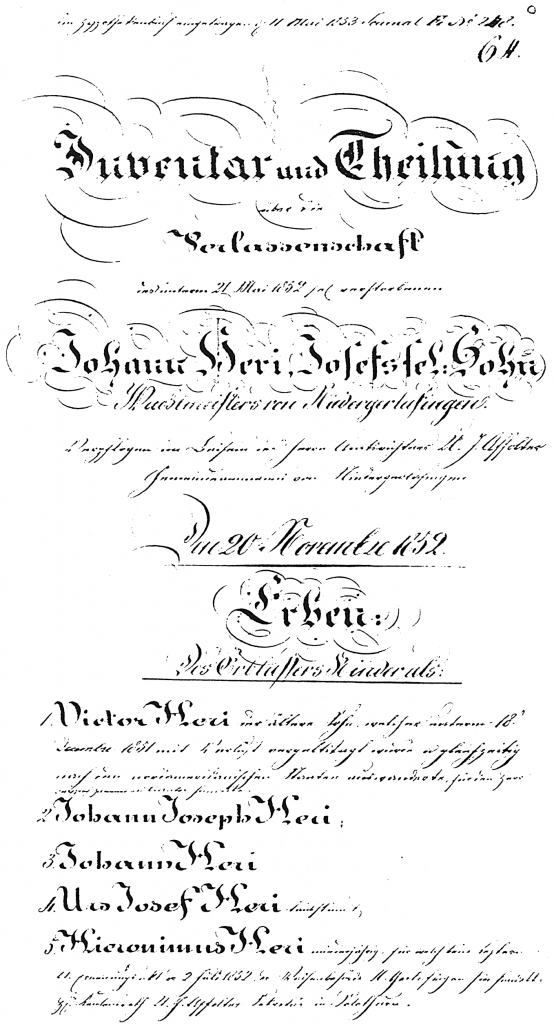

Johann died on May 21, 1852,[13] little more than three months after his son Viktor and his family arrived in the United States of America. He had served in Napoleon’s army, been “Wachtmeister” (chief of the watch) of the town, and lived out his life as a farmer. By the time of his death, Johann had accumulated a great deal of wealth so as to be considered wealthy by the standards of the time.[14] His worth at his death was 21,418.73.

The way Viktor claimed to have received news of his father’s death was unique. One day while the family was still living in Dubuque, Viktor came into the house and announced to his wife Mary, “Well, my father is dead.”

Mary asked, “How do you know?”

Viktor answered, “I heard the bells in the old country ringing for him this morning.” Not long afterwards, Viktor received the message which told him of his father’s death on the day he heard the bells ring.[15]

The fact that Viktor first learned of his father’s death by hearing the bells ringing for him several thousand miles away foreshadows the later claim by John F. Harry (born: 1878) that he would hear three knocks when a relative died. Actually, this is not an unusual phenomenon among some Swiss. It is expressed in the phrase “Die Toten genoden (melden) sich” [The dead give notice of themselves].[16]

The death of Johann was a serious blow to the family, for he had promised to help Viktor by sending money to assist his start in the new country. When Johann died, the promised assistance did not come.[17] Records in Switzerland indicate that Viktor was to receive 4,283.75 of his father’s inheritance of which 158.55 was paid.[18]

Footnotes

[1] There is some confusion with the name of this Heri in the 1961 family history. In that account, the Heri fighting with Napoleon’s army is named “Josef.” However, his year of birth and year of death prove that it is Johann Heri being spoken of.

[2] History of the Harry Family” 1961, p. 1.

[3] History of the Harry Family” 1961, p. 1

[4] History of the Harry Family” 1961, p. 1-2.

[5] The Anabaptists were prohibited in Switzerland at this time. Each parish in the Reformed (State) Church appointed an “Ehegaumer.” One of the principle duties of this person was the enforcement of the law which required every child to be baptized in the state church within a few days after.

[6] Conversation Beat Heri of Zurich had with author in May 1997.

[7] Festschrift zur Weihe der Bruderklausenkirche Gerlafingen an 2 Dezember 1956.

[8] Kriegstetten-Schreiben 1832, Bd20, p. 151ff Sig AC 4, 20. The original sheets of testimony, including signatures of those testifying, are at the Staatsarchiv des Kanton Solothurn. The translations quoted in this book were done informally in June 1997 from transcriptions Beat Heri of Zurich had done from the originals.

[9] Viktor was actually 15 years old at the time.

[10] Beat Heri of Zurich to author during a visit to Beat’s house in June 1997.

[11] The translation of the German is The Builder Johann Hery. I learned of the location of Johann and Maria Heri’s residence in 1982 during a conversation with Herr Friedli, a historian from Gerlafingen. He was doing research in the Staatsarchiv when we were introduced in the summer of 1982. He claimed that the house had been torn down a couple of years prior but suggested that I could locate the property because it was on the main street of Gerlafingen and now contained a gas station, grocery store and apartment building. You can imagine my excitement, walking towards the gas station and finding it housed in a typical old Swiss house. At the 1985 family reunion in Alma, Wl, I showed Beat Heri from Moraga, California pictures of the house I thought was once the home of the Johann and Maria Heri Family. He called Switzerland to have a relative check the building out. This person went to the the building and discovered the beams, proving that this was indeed the family’s residence.

[12] When I visited Switzerland in June 1997, Beat Heri drove me to his home outside Zurich. I mentioned that I was disappointed to learn that the house in Gerlafingen had been tom down and the inscribed beams destroyed. Beat said that he had been in the ammy at the time and could not get to Gerlafingen to save the beams. However, he had since reamed that others had removed the beams before they were destroyed. In fact, he had one at his house and would be happy to show it to me. In his computer room, leaning up against the wall is the approximately four foot long beam that indicated to visitors for over 150 years that Johann Heri built this house!

[13] Inventar und TheiIung, Staatsarchiv des Kanton Solothum

[14] “History of the Harry Family” 1961, p. 3. There were other indications of Johann’s wealth. When his home burned in 1831, one of the Kanton officials mentioned in his testimony that “the man who lost his house is rich.

[15] “History of the Harry Family” 1961, pp. 22-23.

[16] Elisabeth Heri to author during a visit to her home in 1982. She remembers times when she was told to pray for the soul of a relative who had just died and only afterwards would the family be notified of that person’s death.

[17] “History of the Harry Family” 1961, pp. 23.

[18] Beat Heri to author during a visit to his house in June 1997.